- Home

- M. Allen Cunningham

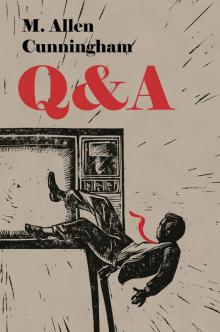

Q & A Page 5

Q & A Read online

Page 5

“Ready for your sixteen thousand dollar question?”

Always a mirror.

Who’s at the switch?

What happened to the signal?

CONTROL

Full-front is Fred Mint’s strong angle—trim figure, features sharp, chin like a rock. When he turns you see his slight hunch and the face in profile goes doughy.

—Pull in, Camera One, nice’n slow—

He faces the camera now, looking you in the eye, close as a kiss, dapper tie done up snug.

—There, hold it, that’s beautiful, and—

“Good evening. I’m Fred Mint. For six weeks on this program a twenty-nine-year-old college student, Sid Winfeld, has beaten all his opponents and run his winnings up to sixty-nine thousand five hundred dollars. Hundreds of people from around the country have offered to challenge him. Tonight some will get their chance to do so, and during the next thirty minutes we’ll find out whether they can win against the unstoppable Winfeld. So now”

—Ready Camera Two—

“presented by Geritol, America’s Number One Tonic, let’s meet our first two players. From New York City, Mister Kenyon Saint Claire, and returning with sixty-nine thousand five hundred dollars from Queens, New York, Mister Sidney Winfeld.”

—Camera Two—

KENYON

Dark in the wings, hurriedly finishing a smoke, Kenyon watches the silver face illumined on a monitor overhead, the voice transposed to a distance of several yards, Mint himself facing away in the bath of light beyond the booths. Tonight some of these people will get their chance, Mint is saying, though Kenny alone stands by in this dark, the floodlit contest to come already decided. Or so he’s understood. In which case, why so horribly nervous now?

Somewhere opposite, in the dark behind the other booth, stands Winfeld, watching him perhaps, Kenny’s own face lit gold with every pull on the cigarette. Does he know, poor Winfeld, what’s coming? Surely he does. Surely they’ve made it worth his while, the arrangement settled. He and Kenny are to shake hands afterward, in the light before the cameras as the audience applauds.

And they’re applauding now, and here goes, and Kenyon drops his smoke into the Dixie cup an assistant offers. Moves ahead into the light and there before him materialized like an image in a mirror is Sid Winfeld, small and stout in oversized jacket, tortoise shell glasses gone milky in the brightness. Eyes averted, the players pivot to pass shoulder to shoulder between the booths. Four steps forward in the lens glare and static of clapping hands to find their footmarks beside Mint at the podium, to crowd in and stick for the three-shot as instructed. The camera’s red light is a hungry eye fixed upon them.

“Welcome back, Sid Winfeld, and a cordial welcome to you, Mister Saint Claire. Now Sid, you’re faced with that same awful decision that begins every game. You have sixty-nine thousand five hundred dollars. You can take it and quit right now and a check will be waiting, or you can continue playing. Of course, if you go on playing and Mister Saint Claire beats you, his winnings will be deducted from the money you have. So, to help you make up your mind, here are some things you should know about Kenyon Saint Claire.”

Now a second camera lights up red, pulling in close on Kenny as the voice of Bob Shepherd, low and weirdly intimate in register, comes over a microphone from somewhere in the darkness above. It’s like a voice in one’s head: He teaches music at Columbia University and was a student at Cambridge University in England. He’s written two books and is currently working on his third, and his hobby is playing the piano in chamber music groups.

They said to look in the lens, but Kenyon can’t do it. He can feel the frame pressing in around his head and strives to compose his face in its cake of blush and powder, sweat already beading in his hair. Teaches music, did they say? A student at Cambridge for a time perhaps—but three books? And as for the piano, how his family would laugh: at most he’ll sometimes noodle around after dinner on his parents’ old upright, cigarette still in hand. But now Fred Mint is turning to address him.

“Out of curiosity, Mister Saint Claire, are you in any way related to Maynard Saint Claire up at Columbia University, the famous prize-winning writer?”

There’s a burning in Kenny’s throat. Did he put out his last cigarette or swallow it? He stoops, one hand resting awkwardly on the wing of the podium where his microphone is mounted. He feels he can’t possibly be squeezed into the same shot with these two men, over whom he towers by a head.

“Um, yes I am,” he answers. “Maynard Saint Claire is my father.”

“He is your father!”

“Yes.”

“Well, Saint Claire is a very well-known name. Are you related to any of the other well-known Saint Claires?”

He needs to swallow but his throat won’t function—anyway they’re reeling the words right out of him.

“Uh, well Emily Saint Claire, the author and editor, is my mother, and Curtis Saint Claire, the historian, was my uncle.”

“Curtis Saint Claire. Also a prize-winning writer, wasn’t he?”

“That’s right.”

“Well, you have every reason in the world to be proud of your name and family, Mister Saint Claire. Now, Sid Winfeld, you’ve heard some things about Kenyon Saint Claire. You have sixty-nine thousand five hundred dollars. Do you want to take it and quit, or risk it by playing against him? What’ll it be?”

“I’ll take a chance, Mister Mint.”

“That’s the spirit, Sid. OK then, gentlemen, take your places in the booths. Don’t forget to put on your earphones, and good luck to both of you.”

Music sounds. The hot lights are on. Turn now, through the narrow door, into the glass box. There’s the upright microphone, slender as a charmed snake. The shut door muffles the studio orchestra and seals in the heat. A private terrarium, televised. The camera’s red eye in the dark, the viewers beyond the lens. How many? Duck to don the headphones and all is doubly muffled. Inward and inward inside the glass, deaf to the world that watches.

CONTROL

As the players enter the booths, twin spokesmodels appear as though conjured by the music. Affixing each contestant’s name to his scorebox, they glide back on their heels, withdrawing, every movement synchronized. The music ends.

“Neither player in the booths can hear anything,” says Fred Mint, “until I turn their booths on—which I am going to do right now.”

KENYON

A click in Kenny’s ears, then Mint’s voice coming through like a telephone: “Can you hear me, Sid Winfeld?”

“Yes I can,” answers the other voice.

“Mister Saint Claire?”

“Yes, loud and clear.”

“All right Sid, I’m going to turn your booth off. I’ll be back to you in just a moment.”

Click.

“Mister Saint Claire, I think you know how to play this game. You try to get twenty-one points as fast as you can by answering questions with a point value from one to eleven. The high-point questions are difficult, the lower-point questions a bit easier. The first category is World War Two. How much do you think you know about World War Two? You can tell us by saying how many points you want from one to eleven.”

You’ll take seven, Lacky had told him. You’ll tie the first round.

“World War Two,” says Kenny, as if contemplating. “I’ll try seven points.”

In their dry run, to his own surprise, he’d answered a number of Lacky’s questions correctly. You know what you know, and we know what you know. It’s simple. Lacky’s office doors shut and Lacky on his feet before the desk, dabbing his brow with a handkerchief. It’s gonna be hot in there, that I can promise you, so after the big questions you’ll press your face like this.

Already Kenny can feel the sweat around his eyes. The questions he missed he went and looked up on his own. We help you be you, even on televi

sion. And here comes Lake Ladoga.

“For seven points,” says Mint’s voice. “Lake Ladoga played a large part in a particular phase of World War Two. Name the countries whose troops opposed each other at Lake Ladoga.”

Isn’t that more of a geography question? he’d said to Lacky. It’s Finland and Russia that border Ladoga, of course.

Lacky just gave him a look. Geography or war, what sounds more exciting, Kenny?

“Let’s see,” says Kenny. The words in his own earphones are like an inner voice and every deep-drawn breath booms in the mike and he knows the mike feeds his voice to the camera and the camera feeds the television sets—how many?—all speciated around the country. “Let’s see, I remember the German-Russian line ran from Lake Ladoga to the Black Sea, but Ladoga, I guess it’s in Finland, so would the answer be Finland and Russia?”

“It would be,” declares Mint, “and you have seven points!”

And here comes the audience applause, and Kenyon breathes and smiles, his smiling face so tight with makeup it’s like a mask he can’t quite crack.

Then click, the applause is gone, Mint turns his back, and Kenny is alone and left to wait in his light behind the glass.

COMMENTATORS

“You want the viewer to react emotionally to a contestant. Whether he reacts favorably or negatively is not that important. The important thing is that he react. He should watch hoping a contestant will win, or he should watch hoping a contestant will lose. … People tune in to see someone unpleasant defeated.”

LIVING ROOM

Wouldn’t be all that bad to see this new fella win.

The picture switches to Sid Winfeld. Bloodless gray behind glass, greased hair askew under his headset, he takes the ten-point question, sweating visibly around his mouth.

Get the guy a hankie.

“Sid Winfeld, you’re right—and you now have ten points!”

Applause, and Sid in his booth pumps both fists downward as if a landing a jump. His lighted scorebox winks—the numeral 10 appears.

Just might be unbeatable, this guy.

Fred Mint flips his lever and turns again to Kenny. “Kenyon Saint Claire, you have seven points.” Ding! goes a bell as he snaps up another card. “The second category is The French Revolution. How many points do you want from one to eleven?”

“I should take eleven but I don’t dare. Let me try for ten anyway.”

“Ten points. Here is your question. The French Revolution brought to prominence men of varied backgrounds. Name the following: first, a lawyer nicknamed The Incorruptible, whose idealistic views ironically encouraged the Reign of Terror. Second, a lawyer who as Minister of Justice under the convention advocated The Revolutionary Tribunal.”

This one’s a doozy.

“Third, a physician scientist who published a revolutionary journal called The Friend of the People. And fourth, the man who was considered the greatest orator of the constituent assembly. He was of noble birth and his aim was a constitutional monarchy.”

“Oh my goodness! Well, my father would know that.”

He’s smart but not uppity, this fella.

KENYON

Through the earphones Kenny hears the ambient ripple of laughter from the audience. Amazing, but they’re pulling for him already, the laughter a delicious warmth in his head. He smiles at the sound and coughs a laugh of his own into one hand.

Should I really say that about my dad? he’d asked Lacky.

Just try it, OK? They’re gonna root for you, you’ll see.

“It’s a four-part question,” says Mint’s voice. “First, the name of the lawyer nicknamed The Incorruptible.”

“Yes, of course. He said, ‘The King must die that the nation may live.’ That’s Robespierre.”

“Right. Second, a lawyer who as Minister of Justice…”

There’s that statue in Paris, have you seen it?

Lacky’s mouth twitched, a deadpan look. Can’t say that I have, Kenny, no.

“Well, the thing I remember about him,” says Kenyon into the mike, “is the wonderful quotation on his statue. ‘After bread, education is the primary need of the people,’ it says. That would be Danton.”

“That is right,” says Mint. “And indeed you’re proving his statement was true.”

Again comes an encouraging chuckle from the audience, positively electric amid the fuzz of the headset, and Kenyon can’t help smiling in the hot light as he blots his brow and eyes.

“Third,” says Mint, “a physician scientist who published a revolutionary journal called The Friend of the People.”

“Yes,” says Kenyon, on a roll now, and every bit a teacher whose father is a teacher too. “Yes, that paper was very important. It got the people behind the revolution. That has to be Marat.”

Poor Marat, they found him in the bath, sunk down in his own blood.

Huh. Killed himself?

No, stabbed to death. There’s that painting by David.

Let’s not touch on all that. It’s enough to say, what was it, about the people?

His pamphlets got the people behind the revolution.

Yeah. That’s plenty.

“That’s correct,” says Mint. “Fourth, and finally, for your ten points, the man who was considered the greatest orator of the constituent assembly.”

“Well, this one I’ll have to guess. I suppose the greatest orator there was…”

Count to four. One. Two. Three. Four. Like that. Then blurt it out like you’re positive.

“The Count de Mirabot.”

“You’re right for ten points—which brings your score to seventeen!”

And here comes the applause in a great surge of relief. Kenny can hardly understand it, but how clearly they’re on his side, how lucky they seem to feel, as if he carried them through. He’s blotting his face, their roar in his ears, and even in the claustrophobic swelter, the sweat down his back, there comes a cool rush, a chill.

Click.

SIDNEY

“Sid Winfeld, you have ten points,” says Mint, that hopped-up voice in Sidney’s ears. Then the little ding! of the bell and: “The category is Medicine. How many points do you want?”

November twenty-eighth tonight and that makes six weeks running he’s stood in this box, sweating in the old maroon coat and the earphones clamping his skull while he bites his lips, twiddles his fingers on his chin, squeezes his eyes, grimaces, shakes his head, counts to four, always to four. Well, small price to pay, all that.

“I’ll try seven,” he says.

Small price to pay for a run like this, the prize money, the recognizing, all those looks when he walks the campus to classes, the chance to show he knows a thing or two, Sidney Winfeld and his copious memory. Small price, albeit he won’t deny there’s been hiccups—the prize money for instance.

“For seven points, Sir Alexander Fleming and Doctor Selman Waxman are each associated with a famous and potent antibiotic. Name these two antibiotics.”

The prize money—talk about a hiccup—and that long involved speech from Greenmarch last week as to how the sponsor only pays them a flat sum and he’s got his budget to consider or there’s no show and so on and so forth, which the gist was telling Sidney in so many words, we never said you’d keep ALL the money, and serving up the paper he called “the settlement” or something to that effect for Sidney to sign where it stated On winnings from sixty to eighty thousand I will take fifty, eighty to a hundred thousand I will take sixty and such like.

He’s counting now. One. Two …

It’s entertainment, said Greenmarch. A show. There’s the prize money, then there’s your net take. And anyway, you’re already well beyond the twenty-five we first discussed, which gives you no ground to be fussy.

And if I’d rather not sign? said Sidney.

To which

Greenmarch only grinned, a look like poor sap, and said, Let’s remember whose show this is.

Three … Four …

It was all on account of the advance, no question. It had been, what, only three days before that Sidney came asking for the eight and a half grand. Four weeks he’d been on the program, it’s only reasonable he’d want a retainer, so to speak, his winnings piling up with every game but until then not a buck in his pocket. Well, Greenmarch couldn’t shake him till he had a check. Deposited that night and Sidney and Bernice, how they’d fucked after that, like honeymooners.

Five … keep them waiting, show them real suspense. Six …

“Sir Alexander Fleming,” says Sidney into the mike, “is a discoverer of Penicillin notatum, or Penicillin.”

Notatum’s just icing. To show them up there in the control room that Sidney Winfeld’s the real thing, not some little project of theirs.

“Right,” says Fred Mint. “And Waxman?”

They think Sidney doesn’t see what’s happening here?—the wheels they’ve got in motion now, Mister Professor over there all dressed and done up for the big debut.

“Selman Waxman is the discoverer of Streptomycin, for which—”

“You’re right!” says Mint, cueing the applause to drown Sidney out, but Sidney ain’t through speaking and bears down on the microphone almost shouting—

“For which—”

“You don’t hafta say anything more, and you now have seventeen points!”

“For which he received the Nobel Prize!” The producers anyway will hear him, applause or no—they think he didn’t know Selman Waxman already? And Sidney smiles so they’ll see it, sweat-drenched and boxed up in their tank as he is. But he knows now to do it, the minute the cameras go off, backstage at the first opportunity he’ll get Lacky or Greenmarch off to the side and demand another advance—tactful, professional, but not to be brushed off or denied—ten thousand dollars, he’ll say. I’ve earned it, he’ll say. You owe me.

Q:

How much did you receive in total

as your winnings?

A:

Forty-nine thousand five hundred, sir.

Q & A

Q & A