- Home

- M. Allen Cunningham

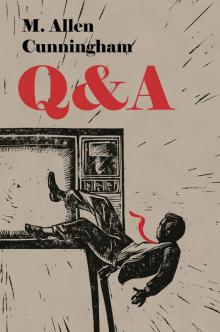

Q & A Page 4

Q & A Read online

Page 4

He stands at the large living room window that looks out on the twilit park and wonders, not for the first time, about the varying altitudes in New York: their differing qualities of light, sound, vibration. Underground. Street level. Office. Penthouse. Pigeon roost. The city itself strikes him sometimes as an act of patricide on a vast collective scale. Its main idea is dominance. And now a change in the focus of his gaze reveals him to himself in the glass, his transparent figure stretched massively over the park. But he is only one framed human, he knows, in a grid of identical frames.

This is how we store our people here, thinks Kenyon.

Last night he dreamt he was walking all around the city, weak with anxiety, taking many wrong turns. Threatful figures awaited him in alleyways. Lost, dazed, he’d found himself inside a greasy bottling plant or pump room, crud-caked pipes and valves in all directions, endless flights of metal stairs. Then: standing on a sidewalk before the great wooden doors of a church, talking to a bystander. It’s the strangest thing, he’d said, to be in a place so familiar and to feel totally lost. He’d awakened himself speaking these words, after which he lay for a time in the dark, amazed by the fluency of his articulation, the clarity of his own voice that had carried him over out of dream.

Kenyon is remembering this when he becomes aware of someone beside him at the window, a small dark figure in the glass. A voice says, “Helluva view, ain’t it?”

Sam Lacky is a small man, something boyish about him, energetic, except with a suave composure. His suit very nicely cut, his cufflinks large, he carries his cigarettes in a silver case. His hands are manicured, smooth-looking, hairless. Kenyon notices the hands first thing. They draw the attention. Clearly Lacky is comfortable in this setting, the people here are his people. But he seems, somehow, apart from it too. He is in television, he says, his company develops the trivia shows.

“I don’t own a set myself,” says Kenyon. But he’s heard a little about these programs. The players answer questions for cash prizes, much like some of the old radio shows. Kip Fadiman, Dad’s old friend, had hosted such a show when Kenny was a boy. Information Please, they called it. The idea was to stump a panel of experts, whereupon you’d hear the ring of a cash register, which meant that whoever had submitted that question had just won twenty-five dollars or some amount. Unforgettable in a way, the clank and chime of the drawer serving up its money.

Lacky is apparently a great information gatherer: already he knows several things about Kenyon. You live in the Village, he says. You’ve written a novel. You and your father both teach at Columbia. For a moment or so Kenyon feels like the evening’s honored guest. Has Clover put this in motion? Has everyone been briefed? One hears that this is the way of things, that those who rise rise first by association, but how strange to go into a setting brightly aware, to stand here, how many stories up, and feel yourself being lifted. Dad’s name, Uncle’s name, these naturally play a part, but Kenyon knows that would only give his father joy—Dad has always wanted passionately all the best for Kenny and George, and he worried, Kenny could see, more than he’d ever admit. When it became clear that Kenny would join the Columbia faculty, Dad wrote him: The rewards, I don’t need to tell you, are scandalously slight. I have enjoyed it, even though I am quitting soon; but the enjoyment was the greater part of my pay. Honest, earnest father—if his name proves a help to his sons, then that, as he sees it, is the higher value of his winning The Prize. What else could The Prize be to a man like Dad but a general glow upon the family, a light in which they all might warm themselves?

When will Kenyon’s novel be published, Lacky asks. A difficult question, but Kenyon answers, “Well, I’m still working on it.” They talk for maybe half an hour. Because Lacky is holding no drink, nothing in his hands but a cigarette, he has nothing to divert his eyes. There’s a deliberate steadiness in his look. “Do you ever find it hard,” he says, “to share your dad’s office?”

And just then their hostess rings the dinner bell, and Lacky and Kenyon turn to fall in with the stream of guests. Leaning, Lacky murmurs, “What do you make over at Columbia, Kenyon? Mind if I ask?”

Kenyon does mind, of course, but he also feels a strange and defensive pride in furnishing, immediately, the figure: $4,400 a year. Because Lacky ought to know that the figure is not why one becomes a teacher. If Lacky hears his answer—and he must—he gives no sign.

One evening early the following week Kenyon answers the phone and there is Sam Lacky’s voice on the other end.

“Penelope gave me your number. I hope you don’t mind.”

Who Penelope is Kenyon doesn’t know—another friend of Clover’s maybe? Clover herself has gone to Los Angeles for some months on business. “No, no,” Kenny says. “How are you, Sam?”

“Well, I’m calling, Kenny, because I believe you’d be a fine fit for one of our shows. What would you say to coming on up to our office to try out?”

“A trivia program, you mean?”

“That’s right. See, we’re looking for new contestants and you’re the first I thought of. I’m convinced you’d have a great success.”

“Well, Sam, I have my teaching.”

“Shows are in the evenings.”

“I’ve never even seen the programs, to tell the truth.”

“You know, they’re entertainment. A man of your education, you’d do fine. And you’d send a very positive message.”

“I’ll give it some thought,” says Kenny.

“Let me buy you lunch,” says Lacky. “What do you say? Are you free tomorrow?”

Here comes Kenyon Saint Claire, thinks Kenyon Saint Claire, approaching his own shrunken figure twinned in the dark lenses of Sam Lacky’s sunglasses. The men shake hands, there on the sidewalk in front of the luncheonette at Madison and 63rd. “Damn, am I glad to see you, pal,” says Lacky. This familiar manner is so perfect a non sequitur that Kenyon can only smile—his walleyed image in the lenses unmoving amid the swim of the avenue.

Inside they order sandwiches and coffee. Lacky pays the ticket. They sit.

“Lemme get right to the point, Kenny. One of the trivia shows I co-produce needs a new contender. Short story is, there’s a guy from Queens goin on five weeks now as the big winner and it’s time to freshen the bed, so to speak. People like a winner, sure, but not all winners are a bag of laughs, and this particular person is starting to … well, worry the sponsors. Now, here I am at this dinner party last week, and here’s this sharp young man from a good family, well-educated, such a believer in education he’s doing the Lord’s work like his father before him bestowing knowledge on the next generation, even though—and you’ll excuse me, Kenny—even though a man can’t raise a family in New York on the salary they’re paying him. So I meet this young man and I think, you know what a man like that is? A man like that is a winner. He’s a winner. He’s doing all the right things, got all the right values, why shouldn’t he be rewarded for it? See, I work in television, Kenny, as you know—but what you may not know is what kinda stuff people are seeing on their TV sets at night. Well, let me tell you, OK? What’s today, Tuesday? Take a typical Tuesday night on ABC, what do you get? Seven-thirty to eight-thirty, Cheyenne. Guns. Eight-thirty to nine, Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp. Guns. Nine to nine-thirty, Broken Arrow. Guns. Two hours of guns and that’s just Tuesday nights. Now, we’re talking tens of millions of viewers, Kenny, tens of millions, and that’s what we’re giving them? Cowboys and Indians? When you start thinking in those numbers, especially if you’re somebody of your very educated nature, it’s pretty demoralizing, wouldn’t you say?”

“Well,” says Kenyon, “at the least it’s a wasted opportunity.”

“A wasted opportunity, that’s right. A real travesty too. I work in the business and even I would say so. But then I meet a young man like yourself, Kenny, and I think, here’s the real thing, here’s the kind of person we ought to see on our television screens

. I’m thinking, I could work with this guy. Now, hear me out. Our company, Mint and Greenmarch, we produce a very different kind of programming. Is it entertainment? Sure. It’s even thrilling in its way—but these thrills, you could call them intellectual in nature. Not a gun in sight. It’s all about what’s happening in the heads of the contestants, it’s all about knowledge. They’re called trivia shows, but you know better than I do, you being the teacher and all, that education is no trivial thing. I don’t know if you’ve ever watched The Sixty-Four Thousand Dollar Question, Kenny, but they’ve got this slogan on there, goes, ‘Where knowledge is king, and the reward king-sized.’ Well, that’s very nice and all, but in point of fact the show’s just onesy-twosy, little questions come and gone—real trivia, you know, and the rest of the time it’s Hal March standing around shooting the breeze or telling the ladies about Revlon. Everybody’s got their sponsor, sure, and that’s all well and good, but our shows are doing something different, doing more for the public, I say. And it’s entertaining, like I say. Don’t get me wrong. But even Shakespeare’s entertainment, you know. No, what Mint and Greenmarch is doing, really, is to push this medium forward—TV being a very young medium, see—and we are confident that a higher level of programming is possible. Take one example, we produce this little children’s program, Winky Dink and You, it’s called, and it’s the nature of this show that kids don’t just sit and stare at the television, but that they actually participate. All the kids have a little Winky Dink Kit at home, see, which comes with these four magic crayons and this magic window, as it’s called, which is a sheet of acetate they stick right to their television screen. And during the program all the kids are right up at the screen and Fred Mint is helping them draw different pictures and things. Now isn’t that, for example, a beautiful use of this medium, helping kids become artists? Doesn’t that beat the regular TV diet of shootouts and silliness? Well, with our trivia programs, too, the idea is education. What I mean is, we’re showing knowledge to be a desirable thing. Our current champ, this guy from Queens, he’s won himself sixty thousand dollars.”

“Sixty thousand dollars?” says Kenyon.

“And counting,” says Lacky. “Unlike the other show, we don’t stop at sixty-four. Now, like I say, Kenny, I look at a man like you and think, now there’s somebody who deserves that kind of money. See, I’ve given this a lot of thought, Kenny, and I’m telling you, you’re the guy to beat Sid Winfeld.”

“That’s the champ you mentioned?”

“Sid Winfeld, mm-hm. It’s time he goes, he’s making the sponsor nervous. Bring a man like Kenyon Saint Claire on the program, though, and it’s good for everyone concerned. A man of real education, man from a good family who ain’t a snob—the sponsors, the viewers, everyone loves it. And you get to earn some of the dough they ain’t paying you up at the college. You take sugar?”

“Sure.” Between them their small table is a mess of deli papers and napkins. Kenyon watches a solid white cascade stream into his paper coffee cup. “Thanks, that’s plenty. I do appreciate your invitation, Sam. But who’s to say I even manage to beat this Winfeld?”

“You’ll manage, no question. I wouldn’t make the proposal if you couldn’t. Like I say, at the end of the day it’s entertainment, it’s television. We don’t just throw you in there, is what I’m sayin. And no one leaves empty-handed. Worst case scenario, you only do one show, a thousand bucks.”

“A thousand?”

“Guaranteed. But you’ll do even better, Kenny. No question. Us producers, our job is to know what you know.”

“Wait,” says Kenny. “Let me understand. You decide who wins?”

“Look, you’re a teacher. We understand that. We’re not looking for actors here, if that’s your concern. You go on to the show as yourself. You’re the educator, the man of good family, that’s you.”

“Yes, but you—”

“We help you be you, even on television. Cause television, it’s a different dimension, see. It’s got its own rules and requirements, every program does, and if you break these, well, there goes your show. It’s a controlled medium or there’s no excitement, and remember, we wanna show the excitement of education. What we do for the program, Kenny, is create people. But the person we’re creating here, well, that’ll be you. You know what you know, and we know what you know. It’s simple, see?”

“I think so. I don’t know. When would this be?”

Kenyon walks to Columbus Circle, following 59th along the edge of the park, turning over Lacky’s words in his mind. Already, somehow, there’s a new clarity in his outlook, a kind of liberating honesty inside him, and it lends buoyancy to his walk along the rumbling street. For the first time in several years, he sees himself plain. What would you do, Lacky asked him, if you won a thousand, a couple thousand dollars? Without hesitation Kenyon said he would write a book. Four words: “I’d write a book.” That’s it. He loves teaching, he believes in teaching—just like Dad—but winning, that is something else. Winning means money, and money means having choices.

And isn’t Lacky right? Wouldn’t Kenyon be teaching while winning?

He’s breathing clear now. He can see himself and own his own feelings. Sometimes, of late, he’s sensed down at some buried level of his being the presence of omens, weird little harbingers, something not right somewhere in his bones, the tremors of a preliminary doom. And now, today, thanks to his selection by the most unlikely of saviors—television!—there is a change. His body moves forward to the subway station, but inside he’s turning about to get a better look at himself, to pose the question to Kenyon Saint Claire, there in the anonymous stream of the New York street: Has it all been a premonition of success?

He’s come to the subway stairs. With sprightly little hops he descends, not even holding the rail, floating down into the roar of the trains and thinking, Sixty thousand! Sixty thousand dollars!

2.

APPLAUSE

November 1956

Winky Dink and you

Winky Dink and me

Always have a lot of fun together

Winky Dink and you

Winky Dink and me

We are pals in fair and stormy weather

All the kids who heard

Winky’s magic word

Make a wish and then they all shall wink-o

What a big surprise

Right before their eyes

Wishes do come true from saying wink-o

Presto change-o, that’s a thing of the past

Wink-o wink-o works twice as fast

Winky Dink and you

Winky Dink and me

Always have a lot of fun together

Winky Dink and you

Winky Dink and me

We are pals in fair or stormy weather.

—Theme song, Winky Dink and You

AND NOW A WORD FROM OUR SPONSORS

“You know ladies,” says the Sixty-four Thousand Dollar Question’s Hal March, looking straight at you as the camera cuts to a closeup, “no matter how often you use a greasy cream or scrub your face with soap—if you’ll forgive my saying this—you still leave some dirt behind. So I’d suggest getting your skin thoroughly clean with…”

Music sounds and a chorus sings: Clean and Clear!

The vertical hold gives way: the picture scrolls upward—

and upward—

and upward…

For a moment the sound is scrambled…

“There must be a moral in this someplace,” says a program host, as the audience laughs. “I don’t know what it is. How many points would you like?”

“Now Helen’s unpacking her Winky Dink Kit right now, getting out her Magic Crayons and now she’s going to get out her Magic Window. Now you do just as she’s doing boys and girls…”

“Revlon puts beauty within your reach,” says Hal Mar

ch, “with Snow Peach!”

“People with low blood iron often feel the cold more, and now that we’re entering the winter season, here’s a suggestion…”

“Watch Helen now, watch as she rubs her Magic Window and you do that too, that’s the way to get some of our magic into the Magic Windows. You see how she rubs it? Fine …”

“Lose ugly fat fast with RDX stomach reducing plan!”

“And now this is Bob Shepherd wishing you good health from Pharmaceuticals Incorporated…”

“Now Helen’s gonna put her Magic Window right up on the screen of the television set. That’s right. Now you do it, just the way she does it, boys and girls, it’s very important …”

“Bill, as if I don’t know, who is Revlon’s next guest?”

“Everyone knows who the sponsor is, but no one is sure who the boss is. The sponsor meets the payroll but that doesn’t make him the boss.”

“We’d sit in the sponsor’s meetings and they would say, ‘Well, that one—that one’s gotta go on to win,’ or, ‘I don’t like that one, let’s get rid of him.’”

The lights are on—

and the lights are on—

and the lights are on …

“You cannot ask random questions of people and have a show. You simply have failure, failure, failure, and that does not make for entertainment.”

“Would you like to win some money now, Meryl?” says Hal March.

“Sponsor, agency, network, producer, director, and even audience—all do certain kinds of bossing at different times and in different ways.”

And in the booth the light is on, and the studio is dark.

“Can you see and hear me, Meryl?” says Hal March.

“Yes I can.”

But this magic window is always a mirror.

Q & A

Q & A