- Home

- M. Allen Cunningham

Q & A Page 2

Q & A Read online

Page 2

“Before we go on” says the host,

—Camera Two—

“I would like to say that all of the questions used on our program have been authenticated for their accuracy”

—Ready Camera Three, real close now, Camera Three—

“and the order of their difficulty by the editorial board of the Encyclopedia Britannica. All right now, Sid Winfeld, how are you holding up?”

—Where’s Sid, fellas? I said Three—

“Just fine, thank you, Mister Mint.”

“Sid, you have nine points.”

—There he is, about time, gents, stay on him now, don’t let’m go—

Ding! goes a little bell as Mint plucks up the next blue card.

“The category is the History of Communications. How many points do you want to try, from one to eleven?”

“Nine please, Mister Mint. I’ll try for nine.”

“For nine points: Who was Samuel Morse’s early partner in the development of the telegraph, and what were the words of their first telegraphic transmission?”

—Hold him now, hold him—

COMMENTATORS

“Some people have said our contestants are too good to be true. Well, the typical American has many facets, and those who doubt it show little faith in the American way.”

Q:

Are all things isolated under glass?

A:

---------------------------

Q:

orever now, will all things be mediated?

A:

---------------------------

Q:

Can you see me? Am I there on your screen?

Am I there at all? Where are we now, and

was it the questions or the answers that led us here?

A:

-----------------------------

Q:

Am I there? Hello?

AND NOW A WORD FROM OUR SPONSORS

If you often can’t sleep your nerves on edge try this new sleeping tablet one hundred percent safe sleep helping to calm down jittery nerves …

“After I did the pilot, we went out to dinner and the sponsor said, ‘We may have to change your name because nobody will believe a man named Sonny who’s giving away all that money.’ And I think I said something like, ‘Well, for the money you’re prepared to pay me you can call me anything you want.’ Anyway, the first night of $64,000 Challenge the announcer said, ‘And here is your host Bill Fox,’ and I stood there for a moment until somebody said, ‘That’s you!’“

“The individual—the one with a surname, the one with a unique personal history and perhaps a few secrets to keep—fades happily into virtual space.”

“It was the most impactful show we’ve ever had.”

“The sponsors probably quadrupled their sales in one year. You’re talking about $100 million.”

“It was a con game, that’s all—a scam from start to finish.”

“I’m telling you, on the nights the show was on, you could shoot a cannon down the street, ’cause nobody was on the street.”

“As a matter of fact, there is no audience, not in reality.”

“I remember one night walking down—walking down on a summer’s night in the streets of New York and the windows were open. And out of every window, I heard the same sound and the sound was the show, our show!”

“There are only some millions of groups in millions of living rooms.”

“The deception we best understand and most willingly give our attention to is that which a person works upon himself.”

Safe sleep, one hundred percent, or your money back.

“Every two minutes of every hour of every day, an image from a camera in Jenni’s apartment was loaded onto the web.”

“We’re all secretly practicing for when we, too, will join the ranks of the celebrated.”

“The camera begins to attract its own subject matter.”

“Tell me the large technologies humans have stopped, diverted, or put a break on.”

“It’s no longer a passive recorder but actively attracts the people it records.”

“I’ve often been tormented by the vision of a future in which we have invented, uh, we have really perfected mass communication to the degree that it will be possible to bind together in one great instantaneous network all the human beings of the earth, and that by a system of translation machines such as we have up at the United Nations, they’ll all be able to understand anything that’s being said…”

“In her FAQ, Jenni said, ‘The cam has been there long enough that now I ignore it. So whatever you’re seeing isn’t staged or faked.”

“… And they’re all tuned in at one moment to listen to a central message—and here are billions of people all listening—and the nightmare is very simple: What are they going to hear? Who’s going to say something worth…? ”

“While I don’t claim to be the most interesting person in the world, I do think there’s something compelling about real life that staging it wouldn’t bring to the medium.”

“Well, I’m all for the multiplication of mass impressions. Now don’t misunderstand me. I just think that at the same time we ought to be trying to work out better and better things to say, as well as better and better ways of saying them.”

“She laughed in a sweet, natural way that was a testament to television existence.”

Three medical ingredients all working together like a doctor’s prescription to help bring safe, natural-like sleep.

“Reality, to be profitable, must have its limits.”

“The world was becoming a television studio and those who wished to rule it would have to become actors.”

“Friends, we don’t have much time. Remember Geritol and Geritol Junior…”

“The age of humanism may be burning off.”

Contains no narcotics and is non-habit-forming. Now don’t you deserve a sound sleep?

“Goodnight everybody—see you next week!”

KENYON

As he comes along the sidewalk toward the family house on Bleecker, Kenyon Saint Claire spots his own reflection in the front window, a passing figure sparkling on the glass. Valise in hand, he’s thirty years old and on his way. Even now he could turn through the gate up the steps inside, receive his mother’s kiss and stand before his father’s shelves while Dad stands at the mirror in the other room knotting his tie. They could ride the train together. But no, Kenyon will keep walking, thoughts to himself. He wants to get to Hamilton Hall in time for a cigarette before class.

He remembers the very early days with Dad in the front room by that window, so often standing there as a boy, head cocked to read the titles on the countless spines along the shelves—the books Dad had read but also those he’d written. Kenny would take them down and admire the title pages. Before he could read he’d understood how Dad’s name looked when made of letters. One cover bore a monogram in gold leaf: MSC. Maynard Saint Claire.

Or younger still: sitting on Dad’s lap at the window, watching people pass by on the street, and Dad’s wise tobacco breath: See them, Kenny? More going by than you could ever count. It’s like a play, isn’t it, how they all go by? Oh, it’s like a great drama. It was a silvery screen, the window, its projection grandly three-dimensional. And that drama beyond the glass—the bustle of bodies and cars—was in some way protecting, consoling. Kenyon would discover that all the great dramas shared these properties: however they might chill or frighten you, in the end they were a form of protection and solace—their effect and intent was just this. Dad did—as Kenyon eventually would—see himself in the scenes out there. But the window was never just a mirror. Something in his father’s deportment, his fascination as they peered through the glass, taught the boy this crucial thing: never just a mirror.

Probably the old fellow watched him go by just now.

Kenyon rounds the corner to the whoosh of traffic on Broadway, the awakening city before him like a stage whose curtain is rising. God, he loves the energy of these crisp golden mornings, the fall air so enlivening, the jaunty march amidst his fellow citizens, and the sense of purpose this town confers on its people.

Through Dad’s unspoken guidance Kenny and his brother were led to understand that they were living and growing up inside a culture. It was just one of a great many cultures but it possessed dignity, intelligence, and a legacy of philosophical, moral, and artistic achievement that it gave to the world for keeps: Shakespeare, Jefferson, Emerson, Whitman, Dickinson. Always Dad had given them books. Robinson Crusoe. Treasure Island. Sherlock Holmes. The tales of Kipling. Mark Twain. The Homeric epics. Tacitus, Plotinus, Plutarch, Epictetus and Aurelius. Darwin’s works, Newton’s works, Voltaire, Dostoevsky, Thomas Hardy, William and Henry James. He never pressed the boys to read them all, they were simply gifts. He wanted his sons to know the gift that the world of literature and ideas could be, to never fear the gift or be intimidated by it.

Andersen’s The Little Fir Tree was the first small volume Kenny read front to back, a nasty old tale as he recollects it now. What were the words? And how glad the little fir tree was when at last they came to cut it down! Where the child reading finds a story about fulfilled wishes, the adult sees a tale of misguided hope and betrayal. Mom, at his arm, must have read it that way, though she never let on.

Reading was luxurious in those first years, an engrossment warm and maternal. Perhaps it still is. How well he remembers, during his Army service, his comfort in keeping Palgrave’s Treasury on his person all the time. The little octavo, green with triangles of red leather at each corner, fit snugly under the flap of his field jacket pocket. That book was a constant gift, and more, a talisman: Kenyon never was shipped overseas.

Now it’s his privilege to foster this lifelong enrichment for his students. This fall marks the start of his second year on faculty. Columbia, imagine! Dad’s colleagues are now Kenyon’s as well: Trilling, Barzun, Miner—or if not yet actual colleagues, then soon to be. Already, surely, he’s no less than their peer. A matter of a few years and he’ll have his Ph.D.

For now, Kenyon earns eighty-six dollars a week. In his own Village apartment four blocks from the family home he eats, nearly every other night, grilled cheese and a fried egg—“Croque Madame,” he calls it, to dignify the act. On the off nights he dines with his folks on Bleecker or eats out. Chop Suey. It is a decent life. Though one could wish the neighbors didn’t bang their cans or let their cats spray the stoop. And he’s happy. He’s happy. He is.

At Broadway he boards the crowded uptown train. Inside the car’s bottled light, hugging his valise and gripping a strap, his body is jostled like all the others. Here below, as the train hurries after its yellow beam, a person becomes anonymous, a body in motion, little else—identity in limbo amid the masses.

Dad had won the Pulitzer at forty-six. Kenny was fourteen and became conscious of friends and relations slapping his back. His back, Kenny’s. Suddenly they were slapping his back and smiling as if something had changed for him too, not just for Dad. And the telephone was jangling. And Dad’s name was in the papers. And one weekend a gaggle of reporters trailed the family clear from the city to the farm in Connecticut. All this woke Kenny up—somehow put an end to his boyhood. And newly awake, he understood that he needed to pay attention now, real attention to the years and to the world and to his place in it all. He began thinking he might have a place, began asking way down somewhere inside himself, what place?

The dank motor-oil smell seeps in through the train windows, the rhythmic clacking of wheels numbs the ears. Isolated lights blink past and disappear. There are tunnels off these tunnels—for the workers or in case of emergency. The darkness between stations is a kind of public sleep. But the city is awake. The city is everywhere above, in motion all the time. Kenyon rises to its streets again at Broadway and 116th and strolls the half-block to campus and to Hamilton Hall—and as he passes through the doors, lighting a smoke as he goes, he can actually feel the anonymity sliding off his shoulders.

“Morning Kenyon,” says a colleague, shoes clapping past. “You’re early today.”

“Am I?”

“Beat your father anyway.”

“Oh?”

The first thing Kenny did in this house was fall down the stairs.

In Dad’s office Kenyon sluffs his overcoat. Installed at Dad’s desk he spends twenty minutes reviewing his notes. Finally he gets up to have another smoke, standing in his jacket at the window. Students are trotting here to there around the neat rectangle of the south lawn, bright and resolute on the paved ribbons of the paths. The morning light seems to frame them with special care here, in the school’s safe enclosures.

Probably the old fellow watched him walk past the house this morning. Why didn’t Kenyon stop? The old house is—always has been—narrow and deep. It pulls you in. Four stories, the fourth they always rented out, on the third a study for Dad, and on the second Kenny and George’s room, which the folks keep just as it was, twin beds neatly tucked in the quilts his grandmother stitched.

The first thing Kenny did in this house was fall down the stairs. The voice is Dad’s. Five or six Kenny must have been when he fell. He doesn’t remember the moment itself. But even now Dad will recite the words—at holiday gatherings, midtown luncheons, picnics on the farm—the anecdote retold as long as Kenny can remember. What’s a family but a swirl of inside jokes, of stories shaped and reshaped? This story, though, is curiously firm, so familiar its words could be a refrain from one of Maynard Saint Claire’s poems:

The first thing Kenny did in this house was fall down the stairs.

And then George, not yet four, famously rejoined: No Daddy, but first he had to go up the stairs.

At hand to hear the boy’s remark was Lionel Trilling, the Saint Claires’ Sunday lunch guest. On the spot Trilling ordained George a high critical intelligence destined for a life of close reading. Friends and relations, upon hearing Dad tell this, always roar and smile. “Way to take the fall for your brother, Kenny!”

And Kenyon smiles as they slap his back.

“Well now, isn’t that Mister Saint Claire?” Maynard Saint Claire bustles in, briefcase under one arm, a steaming paper cup in each hand.

“Morning, Dad.”

“Earlier every day, aren’t you? Here’s some coffee.”

Kenyon checks his watch. The coffee hot in his hand.

“You can’t keep out-punctualizing me, Kenny. They’ll retire me on the spot.”

“You’re the punctual one, Dad. I’m just early.”

“Yes, I saw you go past the house this morning. You ought to have knocked, early bird.” Dad hangs overcoat and hat, digs out pipe from breast pocket, pats his side pockets, bends to his desk drawers. “Oh, but I remember that feeling, that eagerness. It’s a wonderful secret: the fun of it all—the energy teaching can give a fellow.” He shuts the drawers. “Damn! I may have to ask you for a cigarette, son.”

Relievedly puffing, Dad sits, but Kenny remains on his feet.

“Seminars this morning, Kenny?”

“Yes. Shakespeare, then Henry James.”

“The Portrait?”

“Ambassadors.”

“Ah. And how will they take it?”

Kenyon shrugs. “They’re a sharp group.”

“Will you also do The Princess Casamassima?”

“I’d like to.”

“Lionel’s introduction is very good, you know.”

“Yes, I think so too.”

“Poor James. Can you teach them to love him as he deserves?”

“I think I can. I’d like to.”

“Oh, but that’s always the question. Will our young one

s, when they’ve left us, love them as they deserve?”

“You know what I was thinking, Dad? Do you remember when I was in Europe?”

“Mm.”

“And you and Mom couldn’t reach me?”

“Ah, yes. Your prodigal year.”

“What did you two make of that?”

“Well, I told your mother, ‘He will not go to Nineveh. He isn’t the first.’”

“Did she worry?”

“Mother? Oh, she’s a rock.”

“It couldn’t have been easy on either of you.”

“Well, anyhow, we put George on your trail.”

Kenyon and Dad chuckle, Dad perched on the radiator in woolen jacket and trousers, reading glasses tucked in breast pocket, cigarette in hand. Deep smoky laugh, crow’s feet and smile lines. He’s led a happy life. In all Kenny’s memories Dad is a laugher and a mild soul. His poetry, measured and meditative, has the same lightness of spirit. How does he put it in that memoir he’s been toiling on? Good art weighs nothing; it knows its way among the mysteries of wit and humor. Its reference to truth is its smile.

“But you know what I was thinking, Dad? Students of mine, some of them, they seem to struggle with Shakespeare so, as if they’re missing some essential preparation. I wonder if what’s lacking is just some world experience, like what I got in Europe.”

Maynard flicks his ash into the glass tray on the sill. He shakes his head. “Everyone, Kenny, is prepared to read Shakespeare by the time they’re eighteen. As teachers we must remember that, son. At eighteen, you’ve been born, you’ve had a father, a mother, you’ve been loved, you’ve had fears, you’ve hated, you’ve been jealous.” He shrugs, turns up his hands as if to say think clearly, you’ll see it is so.

Oh Dad, demystifier of the beautiful and the grand. For thirty-six years in these Columbia classrooms Maynard Saint Claire has labored to instill the guiding values of appreciation: that the fault is not in Shakespeare but in ourselves, and not a question of being equipped but merely of being alive and awake; that good art weighs nothing; that the word was spoken, and because it was printed may go on speaking and, if only we use our hearts and listen, we will hear it speaking to us.

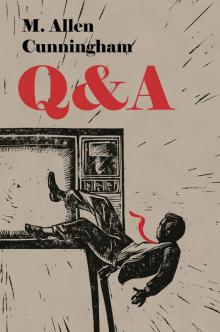

Q & A

Q & A