- Home

- M. Allen Cunningham

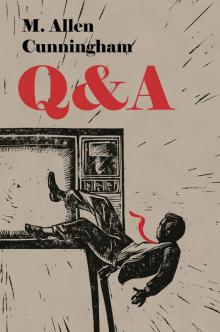

Q & A Page 10

Q & A Read online

Page 10

Who was the viewer?

By some unnerving division that caused a sudden sweat to bloom in his palms as he peered through the glass, Kenyon felt himself standing inside those little screens, in that underwater gray, shrunken in the small booth at Mint’s back, waiting there while Mint spoke to the cameras. The doubleness was almost physical.

When the picture cut to another advertisement, Kenyon went inside. Before the bells on the door had stopped jangling a salesman greeted him.

“I’d like to buy a television set,” said Kenyon.

“Certainly, may I show you the models we carry? Wait a minute, now, aren’t you Kenyon Saint Claire?”

“I am, yes.”

“Well, goodness, what a pleasure to have you visit the store.”

“Thank you.”

“The sets are right this way, Mister Saint Claire. And if you wouldn’t mind, I know that our floor manager Mister Spellman would be delighted to meet you. May I call him down?”

“I’m afraid I’m in a hurry. Perhaps another time?”

“Of course, of course. Our newest models are just here. Each has the latest VHF dial and aerial attachment…”

“This is something of an impulse. I hadn’t planned to buy a set today. Can I pay for this one here and have it delivered?”

“The twenty-one-inch Zenith? Certainly, sir. Are you sure you’d prefer the tabletop model? We do have the RCA console models…”

“This will be fine, thank you.”

To feel so divided—it had frightened him—to be scattered to some space beyond his own recognition or reach. He told himself that by keeping a set he would keep himself close.

The set arrived the following day. The deliveryman unboxed it, placed it in the corner on the low bookshelf whose top Kenyon had cleared, and plugged it into the wall.

“Your first television set, sir?”

“Yes.”

“Simple enough to use,” said the deliveryman, whose jacket was emblazoned with the name of the department store. He clicked a knob on the metal panel above the greenish screen. The television made a bird-like squeak, then an electric hum as the picture emerged, very dim at first, but gradually coming clear: a speckled field like blowing snow. “Volume here,” said the deliveryman. He turned the knob until static hissed, silenced it again. “VHF dial here.” He rotated the dial, but there seemed to be only snow.

“No picture?” said Kenyon.

The delivery man shrugged. “You’ll get something with the aerial. Need to toy with it usually. You have twelve channels, regular programming on three of them: CBS here, NBC here, and ABC here.” Each station, as he clicked through them, displayed a flag-like series of bars and squares. “Mostly test patterns right now. But tonight you’ll get Steve Allen, Ed Sullivan, no problem.”

In fact it would be Kenyon himself on that screen, playing live against Clarence Holloway.

He signed the man’s clipboard and closed the door after him.

He crossed the room to the set and stood with one hand on the dial. The set was warm to the touch and gave off a faint odor of heat, of burning wires. He turned the dial through each snowy station, all twelve. Then he stepped back to stare at the screen as if watching the snow fall outside a window.

Still the photographers circle the car, strands of white exhaust crawling around their ankles.

“Mister and Mrs. Saint Claire,” calls Greenmarch from the sidewalk, “would you come forward for a picture with your son?”

Kenyon hears his father, out of sight, calling back from the crowd. “Is it necessary?”

“Well, sir, it’s not required,” says Greenmarch with a laugh—and the onlookers laugh too. “But you must be very proud.”

Bodies shift about and Maynard and Emily emerge in their overcoats and hats, looking somewhat adrift, in need of instruction.

Greenmarch, loud and charming, says, “Are they always so shy, Kenny?” He’s stepped across to take Emily’s arm.

“I’m afraid so,” says Kenyon.

“Now, won’t you both stand just here beside the driver’s door? There. Oh, that’s very nice, isn’t it.”

Emily’s gloved hand rests on Kenyon’s arm where he’s propped it along the door. Maynard holds his hat in one hand. Kenyon smiles as the cameras clack and stutter.

The onlookers, for some unbeknownst reason, begin to applaud.

Afterward, upstairs in the studio, there is a brunch social with the program team and some members of the press, a crowd of thirty or so. At Greenmarch’s invitation Kenyon’s parents have come up too. Fred Mint is there, and Sam Lacky, and Clarence Holloway, against whom Kenyon will play a third game this week, most likely their final faceoff given what Lacky told Kenyon a few days ago: He’s likeable, but he ain’t a champ. How much does Holloway know about it? Kenyon wonders as he shakes the man’s hand and introduces his parents. He is likeable, Holloway. He has a glass eye and something of a lisp, and a homespun way of knowing his facts. Likeable. Kenyon hardly understood the word the first few times he heard Lacky use it, but now, five weeks on the program and counting, he’s beginning to see what they mean. He himself, apparently, is likeable.

The brunch is a handsome spread of sweet rolls, sliced melon, strawberries, scrolled salami rounds, deviled eggs, olives, and assorted pâtés. All the studio’s utility lights are on and the crowd mingles around the serving table in the space where the audience usually sits, the risers having been cleared away. In this light the set looks absurdly lifeless, one-dimensional. The bulky cameras, pushed against the wall, stand asleep. A small group has gathered around Fred Mint’s podium, plates in hand, glasses propped beside the host’s levers. Kenyon leads his parents on a little tour.

“The dreaded booth!” says Maynard.

“Try it out, Dad.”

Holding his father’s glass as Maynard steps in, Kenyon shuts the door. With Mom he circles to the front. The booth is semi-dark, more like a closet than the specimen box it becomes during the broadcasts. Through the window Maynard waves at them boyishly. They laugh and wave back. Maynard dons the earphones, looking out as he stoops and talks into the mike. Kenyon points to his own ear, shaking his head. “We can’t hear you, Dad. Soundproof!”

“Do we have our next contestant there?” Greenmarch appears at Kenyon’s shoulder, buttered roll and napkin in one hand. “A hell of a show that would be, father versus son.”

Emily chuckles. “Maynard used to have a radio program, you know.”

“Did he?”

“It was some time ago. How long now, Kenny, ten years?”

“Fifteen,” says Kenyon. “Reader’s Hour, it was called. CBS Radio.”

“Is that so? Not a trivia program, I’d guess,” says Greenmarch.

With a mildly theatrical show of relief, Maynard steps out of the booth now. “My God, you feel you’re going to be gassed in there. How do you stand it, Kenny?”

Greenmarch says, “It’s not so good if you’re claustrophobic.”

“I didn’t think I was,” says Maynard. “Now I wonder.”

“And Kenny will tell you, it’s even hotter with the stage lights on.”

“Dad, we were just talking about your radio days.”

“Oh?”

“I never knew you’d had a show, Mister Saint Claire,” says Greenmarch.

“Well, hardly mine. It was a conversation. That was the point.”

“A teaching program, was it?”

“You could say so, I suppose. More precisely it was an on-air book club, a venue for appreciation.”

“Books,” says Greenmarch. “I see.”

“When I say books, of course, I mean … ideas.”

“Mm,” says Greenmarch. “Philosophy and that sort of thing?”

“Philosophy, yes, and literature. Ethics, politics, history, science, religion.”

“How long did it air?”

Maynard’s brows go up. He points a finger at Greenmarch as if to acknowledge he’s hit the bullseye in asking. “Nowadays it wouldn’t, would it?”

Greenmarch chuckles, running a hand down his tie. “Well, I don’t know that it wouldn’t. Just look at what we’re doing here after all. What was your eleven-point question last week, Kenny, the one about the nineteen-twenties?”

“Oh,” says Kenyon, “you mean the one I missed? Uh, four different presidents occupied the White House in the nineteen-twenties. Who were their vice presidents.”

“That’s it. And you got three of them, didn’t you?”

“Mm-hm, couldn’t remember Hoover’s man, sadly.”

“Well, it was a damned challenging question, is my point. And you got three of them. But this is a pass/fail kind of program and three out of four, I’m afraid, does not pass. Now wouldn’t you folks call that a respectable exam? You see, it isn’t all easy questions around here, not by any means.”

“Not easy,” says Maynard, “no. And that’s to be admired. But an answer, Mister Greenmarch, well, it’s not the same as an idea, is it?”

Greenmarch tips his head, nodding as he chomps the last of his buttered roll. “Television,” he says between bites, “is a special medium, Mister Saint Claire, with special requirements. Entertainment—in this line of work entertainment’s the primary concern. You can’t ever afford to forget that your viewers, they’re looking to be entertained. But the trick is, I say, not to become another I Love Lucy—all empty silliness. I say let’s squeeze some knowledge into the entertainment. If we can do that, then we’ve done something. Then everybody wins, I say. See, you and me—the classroom, the TV set—I’m not sure these things are all that different.”

“Squeezed knowledge,” says Maynard, somewhat absently.

“Well, not that it’s a grapefruit or something—”

“And to what end is this knowledge?” says Maynard, with a placid smile. Cool as ever, he will not be roused. As Kenyon knows, though, it’s his father’s lifework they’re discussing—the books he’s studied, the books he’s taught, the books he’s written, and the place of such work in the world. Whether Greenmarch can see this is not so certain.

Kenyon says, “All this reminds me now, Dad, of something I’ve been meaning to propose to Mister Greenmarch and Mister Lacky. Say the program were to include segments on some of the topics that come up in the questions…”

Without even turning his head, eyes still fixed on Maynard, Greenmarch asks, “How much did you win last week, Kenny?”

“Eighty-seven thousand dollars.” To his bones Kenyon knows the sum.

“There,” says Greenmarch. “There’s the answer to your question, Mister Saint Claire. We’re giving your son—excuse me—your son has earned eighty-seven thousand dollars on our program so far. And counting.”

“A great deal of money,” says Maynard.

“Yes, and a fair end result, wouldn’t you say? Television isn’t radio, true enough. But I wonder…” Drawing a breath, turning to Kenyon with a smile, Greenmarch claps his shoulder warmly. “I wonder if your father’s giving television enough credit, Kenny.”

“Oh, I don’t begrudge you your profession, Mister Greenmarch—”

“Call me Ray. Please.”

“I’ve got nothing against your program, Ray. I’m probably speaking out of turn. You see, Emily and I, we don’t own a television ourselves.”

“Oh my! But you’ve watched this fella, haven’t you?”

“Of course,” Emily chimes in. “At our neighbor’s home. We’re terribly proud.”

“I only got a set myself last week,” says Kenyon.

“So you folks saw last week’s program. Now tell me, who was that VP of Hoover’s?”

“Curtis,” says Maynard, just as Emily blurts it out too.

“There you have it. If you’ll forgive me, I’d guess that you both learned a little something.”

“In fact,” says Maynard, “I happen to remember that answer in particular because Curtis is also my brother’s name.”

Greenmarch is deadpan. He turns to Kenyon. “But you mean you went and bought a set yourself, Kenny? We would’ve sent you one! Listen, why don’t you return yours. I’ll get you a set delivered this week.”

“But Ray, I—”

“On second thought, why not keep both of them? One for the bedroom, one for the sitting room.”

“It’s really not necessary, Ray…”

“Nonsense. It’s our pleasure. Consider it done!”

Then, for a moment, they all fall silent, standing under the white utility lights, drinks in hand.

“Well,” says Greenmarch. “Cars, TVs, eighty-seven thousand dollars … Can I get anybody anything else?”

Amid their chuckles Greenmarch claps Kenyon’s shoulder again, then slips away through the crowd.

Kenyon half-expects the matter to be forgotten, but the set from Greenmarch arrives the very next day. It comes in a much larger box than his Zenith. According to the deliveryman, who wheels it on a hand truck, it’s a 21-inch RCA, a beauty with a walnut console and woven speaker. “I hate to be a bother,” Kenyon tells him. “But can I give you another address for this?” He gives the address of the Bleecker house. His parents are spending half of every week in the city now, while his father teaches the spring term.

“How do you like it?” he asks Mom on the phone the following night.

“It’s sort of lovely, isn’t it? It sort of glistens, even when it’s turned off. We’ve put it in the living room.”

“Oh? How’d you find the space for it amid Dad’s shelves?”

“Well, we moved some things around. Anyway, thank you, Kenny. It’s a lovely gift. And how nice to just—turn it on and there you are.”

They’ve watched the night’s broadcast, of course—at last, after three weeks of tie games, he’s vanquished Holloway.

“And aren’t there a lot—we’d had no idea how many programs there are. All the time, so much to see. Does it ever pause?”

COMMENTATORS

“In frenetic quest for the unexpected, we end by finding only the unexpectedness we have planned for ourselves. We meet ourselves coming back.”

“It was the picture that mattered, the face in black and white, animated but also flat, distanced, sealed-off, timeless. … I tried to tell myself it was only television—whatever that was—however it worked—and not some journey out of life or death, not some mysterious separation.”

“Everything on TV is somewhat of a lie, but it’s still entertainment.”

SIDNEY

At the lamplit breakfast table in the dark kitchen, in slacks and undershirt, hair slicked from the shower, Sidney bends forward looking over the photos in the NY Post: Kenyon Saint Somebody in his nice trim suit gooning and clapping his hands as they lay a $3,400 convertible at his feet. And the background—who are all those people in the background so pleased to clap and smile along? What’s in it for them? Even the New York Police have been called out on Kenyon’s account, to hold back the crowd.

For Sidney of course it was never so much as mentioned, such a thing. Not even a consolation prize. Not even a bribe to keep him from spilling the beans. No, for Sidney they never offered a new coffeepot even. Anyway, they counted on he wouldn’t spill the beans, which doing so would only be to spill in his own lap. In other words it was, You want the world knowing you didn’t in actual fact know all those answers? That you gamed them for six weeks running? Give that some thought why don’t you, Sid, was their attitude on that front.

But here they go heaping prizes on Mister Professor—prizes he doesn’t even have to answer questions for, doesn’t even have to earn, while Sidney’s up early to get to the transit office before daylight—a whole day’s work ahead of him and then nigh

t classes after—and here’s the NY Post of all papers reporting on the Professor’s goony smile. They sit on Sidney’s story for a month, then print this instead. Greenmarch is behind that, Sidney’s positive. Dave Gelman, the reporter—hadn’t Gelman said over the phone he’d be calling Greemarch himself?

Sidney folds the paper, pushes away his cream of wheat. That old stomach pain still hasn’t gone. Guzzle Milk of Magnesia by the bottle, no use. And the pain is flaring now, and there’s an angry sweat breaking out under his arms. The day ain’t even started yet, the day’s real work still ahead of him. He takes the folded paper and flings it, throws it hard at the kitchen door but in midair it just flutters open and the pages scatter softly across the floor, the smiling picture of Kenyon Saint Claire coming to rest at Sidney’s feet.

Greenmarch not only reneging on their agreements, not only refusing to take Sidney’s calls, but defaming him probably to Gelman on the phone. Why else would Gelman take a scoop like that and spike it?

And this stomach complaint, which the reason is Sidney being under so much pressure. What does Saint Smiles know, him with his convertible, about pressure like this? All the money gone, gone—what’d Saint Suck-Me ever know about a thing like that? Those thugs and their so-called racing syndicate, the shady dropoff up in Yonkers, which Sidney should have trusted his misgivings on that subject, except that his cousin Arthur was there through the whole deal, Arthur who’d recommended the bookie in the first place and kept saying, Alberto knows these guys, I’m tellin’ ya, though only God knows how well Arthur knew Alberto. And then the guy in the tight jacket crossing the street from the train station to the little gravel lot behind the deli—and before the guy even reached the sidewalk on their side Sidney could see the shape under his jacket, the shape which they were meant to think, hey that ain’t no belt buckle. Right then, who knows what Arthur saw, but Sidney—who’d still had some questions, who’d hoped to discuss further the exact terms and nature of this transaction—could see these guys weren’t the types to leave a meeting empty-handed. So there went the money like they’d planned, awful quick, no more than a minute. The guy took it, checked it, then hooked a thumb and finger between his lips to whistle. From someplace behind them a black car circled around, he jumped in, and goodbye prize money. Arthur thought they’d simply done business, had no idea, and Sidney didn’t say a thing, didn’t even let on, something just drained right out of him and what was the point? Even late as last week, Arthur was nagging him to call them up, check in on their “investment,” and Sidney couldn’t say it clear enough, couldn’t say That money is gone, without Arthur insisting. No, no, you don’t understand these fellas, Sidney. They gotta be like that, but it don’t mean they ain’t good for it. Sidney having told Bernice precisely nada of the whole arrangement, Sidney not sleeping so well lately, Sidney being emptied out and hollow since that handover behind the deli, Sidney’s gut just about killing him some mornings—what’d he do but start to see Arthur’s reasoning. What’d he do but pick up the phone and dial their number. What choice did he have but to hope it wasn’t like he thought. After three rings a woman answered, a secretarial voice, and he was wonderstruck. But he realized he didn’t have an actual person’s name. He mumbled some. Then he said simply, I’m calling to inquire about an investment I’ve made. The woman asked him to hold. There was a click, then silence. A few minutes later he understood they’d been disconnected. He dialed again, and this time, stern-like, the secretarial voice said, You called a few minutes ago, didn’t you? Again she made him hold. And now, after several minutes, a man’s voice came on the line: Who is it?

Q & A

Q & A